Boston Center for the Arts, Center Focus, 2008

Horrigan, Sean, Silent Key (Interview), Center Focus, Boston Center for the Arts Blog, December, 2008

When did you first become influenced by sound as an artist?

One of my earliest memories is of my Grandfather playing 78 rpm records of children’s stories such as The Three Little Pigs. We were prompted to turn the page of the accompanying book by a chime on the record. He also played us Bozo Sings, another old 78 that used odd sound effects. Bozo’s Song featured rather perverse versions of different animals “singing” (and now the seal! “Bozo, Bozo, Bozo the clown!” and now the frog! etcŠ). A few years later I purchased my first 45, Hello, I Love You by the Doors, a bit of a jump in taste I guess.

I was exposed to more experimental forms in the late 70’s via the Punk movement. Mike Watt of the Minutemen worked with me on Fore N Aft, the San Pedro High School newspaper and I was one of those people who “drove up from Pedro” to see shows in Hollywood. I bought Negativland’s first LP in 1980 which had a collaged handmade cover and used all sorts of found sounds. I was particularly fond of track 2 which combined guitar, vacuum cleaner and blender I believe.

Several years later, in 1998, I started producing the sound events and concerts and that eventually became SASSAS (The Society for the Activation of Social Space through Art and Sound) the non-profit I direct in Los Angeles.

Can you walk our readers through the exhibit?

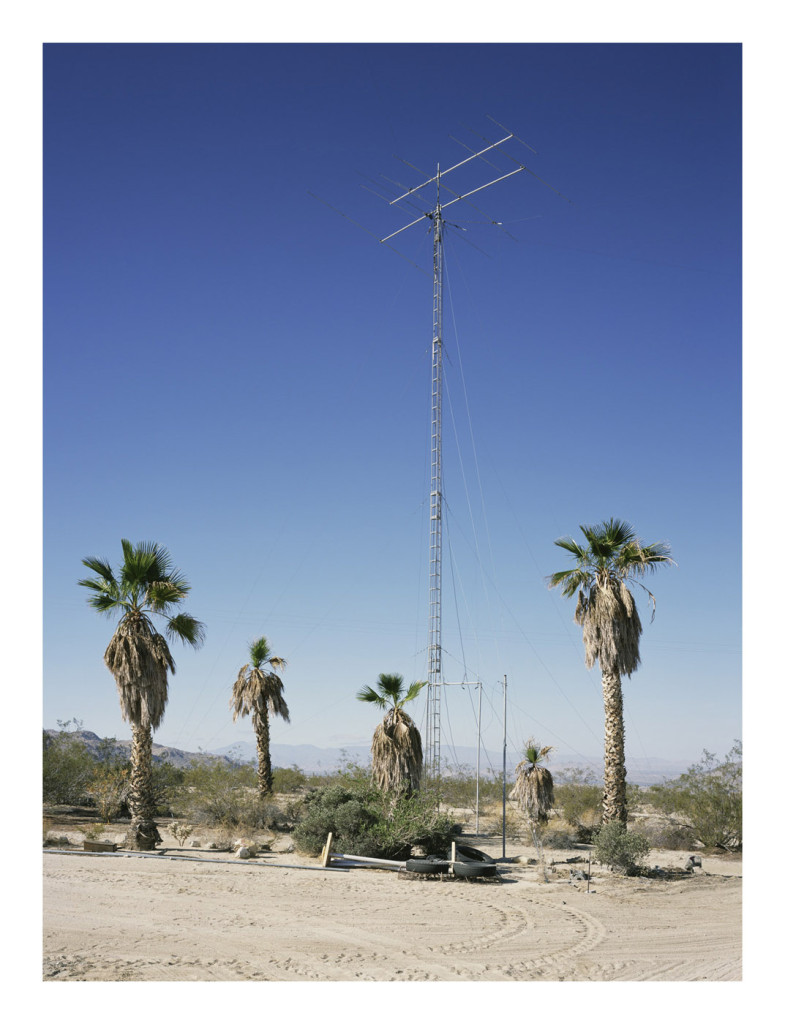

The show is called Silent Key – that’s ham radio lingo for an operator who is deceased. Their telegraph key has gone silent. The show has three primary components: Deleted Entities 1925 – 1996, a 115 part grid that reproduces QSL cards from my Grandfather’s collection, a large photograph of one of the antennas still standing on my his antenna farm in Twentynine Palms, California and Portraits, a series of images of ham radio operators drawn from the QSL cards.

When doing the portraits, I felt it was important to track down some concrete information about the person depicted – the dates they were active as a ham, if they were still active and whether they were a “Silent Key”. I’d always been taken with the image of G. Bell, an operator from Duneden New Zealand. He’s sitting in front of a wall of QSL cards staring directly into the camera in a way that makes you feel as though he’s gazing at you from the depths of history.

Since the card is from 1934, it’s been extremely difficult to track him down. Luckily a friend of mine, the musician David Watson, returned to New Zealand for a visit last summer. I asked David if he would go to the address on the card to see if anything remained. As it turns out, it’s the only house standing on a street that’s now mostly industrial properties. We may include that video in the exhibition as well.

Can you give us a little education on QSL cards? Do they provide a glimpse into history? What can they teach us?

In ham lingo, QSL means “I hear you” or “I acknowledge receipt.”

What’s fascinating about them is they document so many things! They map complex world and personal histories as well as a multitude of design styles and vernacular typography. Researching them was a great history lesson for me.

The function of the cards is to record and verify the technical facts of a communication between two people, yet because of their design and the way the information is conveyed, they are incredibly evocative of specific moments in history.

For this particular project I choose cards from political entities that no longer exist. The cards reflect the last days of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the various Soviet satellite regimes, the Japanese occupation of Korea and China, Colonial Africa, etc. The title of each work cites 3 moments in time the world order of the past as reflected in the entity named on the card (ie “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR)”), the entity as it is known today (“Georgia”) and the date the prior order shifted (“independent 1991”). That in some cases these terms remain unsettled is a sign of the transient nature of political boundaries.

The idea of building the grid based on deleted entitles is derived from a list issued put out by the DXCC (DX Century Club) of entitles that are no longer valid for ham radio contests.

Tell us a little bit about your grandfather; he seems to have played a pivotal role in your life. When did he first form a connection with the ham radio and what kept him connected throughout his life?

Bill Adams received his degree in engineering from Cal Tech and liked to tell the story of being run over by Albert Einstein who used to bicycle around campus. He worked as an engineer for Proctor and Gamble for many years eventually retiring to Twentynine Palms in 1964.

He was very active in the ham radio community. First licensed in 1923, he eventually co- founded the Southern California DX Club in 1947, which was dedicated to contacts occurring over extremely long distances. Community spirit was a part of the ethos of being an operator – there was even a code that was published in the early magazines dedicated to amateur radio.

Have you met many ham operators? Do you find that they share any common traits as a community? Would you compare the ham culture to the virtual communities we’ve created on-line today?

It’s common in the ham radio community to participate in contests. These are usually weekend long events where operators work to make as many contacts in as many countries as can be reached in a specified period of time. For instance the card as I’ve used as the key for interpreting the QSLs was from the first of 525 contacts made in a 24 hour period.

I did meet several of the operators who at gathered at the house in Twentynine but frankly, I was a teenager and at the time, this seemed to be very nerdy activity. In that sense they certainly are reminiscent of the early computer geeks. I regret that I didn’t better understand what they were doing. Lately I’ve been in touch with Jan Perkins (N6AW) who’s been a great help with the project.

I’m always fascinated by who was involved in ham radio – I didn’t know him, but John Weber, a well known gallerist in NY who passed on recently was a ham radio operator. And SST Records is named for a piece of amateur radio equipment designed by Greg Ginn, the founder of the label and of the band Black Flag. He also briefly published a ham radio zine called The Novice.

It’s a misconception that the internet is replacing ham radio, certainly there been an impact but the nature of the communication is very different and unlike most of us who are tied to our computers, amateur radio operators own their own infrastructure.

Let’s talk about the antenna photographs? From my perspective they feel like monuments in the silent desert landscape. What feelings do they evoke for you?

The antenna photos were originally shot for another body of work called Learning to Listen in which I’m documenting traces of a quickly disappearing analogue world. About the same time as I was working on those images, I read a wonderful article in Harper’s, Antenna of the Universe: Grandpa had a thing about good reception by Don Wallace who’s grandfather was of a friend of my grandfather’s and that prompted me to begin a search for the QSL cards.

A friend said that Antenna (NW), W6BA/W6ANN reminded him of a photo he’d seen of ” a scientist sitting down, alone, in Antarctica, making a phone call” and I thought that was a beautiful image.

What role does the logbook play in the exhibit?

This is one of his early logbooks, in which he occasionally makes notes about the content of the communications. It would be easy to imagine that the hams were discussing big issues, but in fact the exchanges were mundane. An entry reads, “He said it was snowing” for instance. For the most part they were discussing what many technically oriented men talk about – their gear. But perhaps this is also what enabled them to traverse the political boundaries which are so often a greater impediment to communication than distance.

Originally published on the Boston Center for the Arts Blog “Center Focus,” December 2008 (Currently offline)

Would you like to share your thoughts?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *